. . . .. ... .... ..... ...... ........ ............

Lockpicking Americans ............ ........ ...... ..... .... ... .. . . .

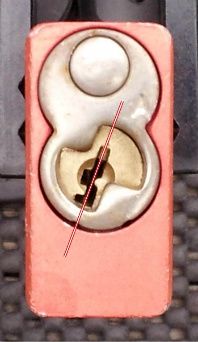

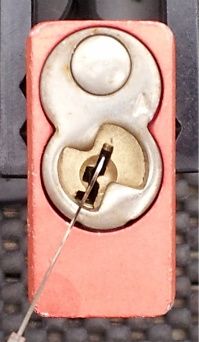

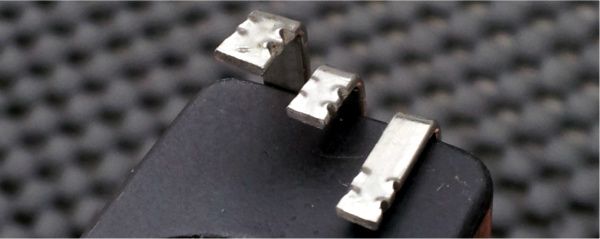

Serrated DriversBefore discussing the

actual picking of serrated drivers, it's only logical we first tryn' gain a thorough understanding of them.

The simplest way to do this, I've found, is to take a look at a standard cylindrical driver in comparison to a serrated driver.

.....versus.....

.....versus.....

Here we have the most basic of driver pins. It has a smooth surface and a consistant diameter from end to end. Such a pin, even

when binding, is easily lifted and slides smoothly across the shearline. In contrast, serrated pins are anything but smooth.

The multiple serrations provide plenty of resistance as we attempt to lift them above the shearline.

More so than resistance, they're designed to confuse and frustrate. As each serration reaches the shearline, we receive

a distinct '

click' that can be heard and felt. This feedback gives us the false impression of a correctly set pinstack.

Also, the depth of each serration allows the plug to turn ever so slightly, causing yet another pin to bind.

This only helps to reinforce our false notion that the previous pin was indeed set correctly.

There is one other thing I'd like to touch on, and I've heard it more than once. The idea is this:

"

by revisiting an incorrectly set serrated driver, you'll inevitably lose ALL previously set pins"

By no means am I saying this is false. There's

certainly truth to this statement, as there will be plenty of times

that this will cause you to lose one, two, or even all of the other pins. (

when this happens, just continue picking...

you're one step closer to reaching the true binding order) However, I've picked a fair amount of these locks, and this

does not entirely coincide with my experience. Often times I find I can revisit a pin, lifting it passed additional

serrations (like it should've been the first time around) and not lose any of my previously made progress.

Picking Serrated PinsSo we now know the problem: "have I truly set the pin, or am I hung up on a serration?"

Our solution must be a method that enables us to reliably differenciate between the two.Once we've acclimated our senses to the subtle differences between a set and a serration,

these pins will become far less daunting than you might think. This doesn't mean that we'll

always be able to pick them with absolute ease

every time... but you may be surprised to

find just how quickly and reliably you can overcome these security pins much of the time.

Sight, sound, and feel, can all play a role. The majority of our focus however, must be placed on feel!

It is by far, our most reliable source for deciphering true from false when dealing with serrated pins.

The other two (

sight & sound) are merely complimentary to feel. They can give us a broader view

of what's going on inside the lock, and also help to confirm the insights we've gained through feel.

Depending on several factors, the feedback we receive from sight and sound can not only be dampend (

or non-existant),

but can even be deceiving. So again, emphasis is placed on feel, and our practice sessions should be geared towards

honing our sense of touch. Bearing this in mind... lets take a look at all three, and how they can help us.

SIGHTI've all but excluded this from my technique, and debated whether it should even be included in this article. However,

you may find it more useful than I, and is therefore worth mentioning. Here's what I'm talking about. The cores in these

locks are seated loosely within the body. This is especially true of the locks within the 1100 Series along with many others.

So much so, that you'll sometimes observe the entire core move upward with your pick as you attempt to lift a pinstack.

If you tend to use fairly light tension with these locks, this core movement

may serve as a useful indicator...

letting you know that the pin is set, and any further lifting will result in an overset pinstack. On the other hand,

if you prefer medium-heavy tension (

as I do), the movement of the core becomes irrelevant and tells us nothing

about what's really going on. We can be lifting a pin past a serration, or lifting a pin that is already set...

and in

both cases, the core is apt to move.

SOUNDSome may downplay this as a viable means of recognizing a serration from a set. But for me personally,

it has proved to be quite useful. Again, it is secondary only to 'feel'. But when I take careful note of what

I'm hearing, and couple it with what I'm feeling, it creates for a devastating combination that allows me to

plow through these locks. Well, not ALL of them of course... lol... but a good majority anyways.

Admittedly, it's rather difficult to put into words. But there

does exist a slight (

but noticable) difference

in the sound produced by a serration as opposed to a set. When a serration hits the shearline, a somewhat

dull '

click' will be heard. A 'true set' however, seems to give off a cleaner, more crisp '

snap'. So if we were

to put this in big technical terms, the picking of one pinstack might go like this: click, click, click, snap. lol

To what degree we're able to utilize sound depends on a couple of things though. Again, tension is a factor here.

We're always looking for subtle differences when picking a lock. As a general rule, the heavier the tension being

used, the more pronounced these differences become. So, if you like to use fairly light tension with these locks,

you may find that sound is not much of a tool for interpretation. The other factor is the condition of the lock.

Some locks have been lubricated many times over the years with both wet AND dry lubricants. The mixture of

the two eventually creates a greasy paste that can dampen or even kill the feedback we would've otherwise

received from sound. Other large amounts of foreign debris can essentially create the same affect.

FEEL Probably the most difficult of the three senses to acquire. But this my friends, is our bread & butter when it comes

to killing Americans. Devote your time and effort... and it will pay off. This may look like alot at first glance, but it's not.

Really, it's more complicated to put into words than it is to do. Just give this a good thorough read and begin experimenting.

We want a good balance between tension and lifting force. But lets look more so at lifting force for a moment.

I'm referring to your pick & the force you use to lift a pin. We're looking to achieve what I call the '

perfect threshold'

-

a lifting force sufficient enough to overcome serrations, yet not so great as to push the pin beyond the shearline (overset)-

Once we've found this optimal lifting force and become proficient with it, it tells us everything!

We'll lift a pin past any serrations required. Yet when the pin hits the shearline and is actually set,

it will feel too hard to push any further... we'll know it's time to leave it alone and move on. Again, the

perfect lifting force allows us to notice this 'hardness' without oversetting the pin. Once more, in big technical,

scientific wording, it'll all play out something like this - click... click... click... HARD. lol

As I mentioned, there must be a balance between tension and lifting force. However, don't be overly concerned with this...

the balance between the two will occur almost naturally. The optimal lifting force will be directly proportional to the amount

of tension being applied. Since we all use a different amount of tension, the optimal lifting force will be different for each of us.

So when you start experimenting, simply use the tension you prefer. When you find the lifting force that produces results for you,

that force will automatically be taylored to the amount of tension you were using when you found it. Just be aware that if the

tension changes, so too will that optimum lifting force that you previously found worked so well.

If you're struggling with this, you may find it beneficial to get to know the lock you're working with. Know the binding order.

And even more importantly... know exactly how many serrations must be past for each pinstack before it's truly set. Now you have

a controlled environment in which to begin experimenting. Your goal: find the lifting force that is JUST SLIGHTLY LIGHTER than that

required to overlift the pinstack. Start out by purposely oversetting a pin. Feel the mushyness that occurs. Take careful note of just

how much force it took to overlift. Then do it again, each time using a little less lifting force than the last. Eventually, you'll arrive at

your optimal lifting force that creates that perfect threshold. I'll touch on this once more in a minute, giving you one more example.

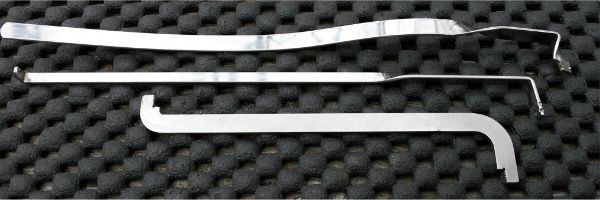

TECHNIQUELets talk briefly about the actual

finding and

lifting of pinstacks.

FINDING the binding pinstack can be done in one of two ways... lets call them '

pattern testing'

and '

sweeping'.

PATTERN TESTINGJust as the name implies, each pin is methodically tested while following a pattern. This insures we don't miss any pins.

That 'perfect threshold' pressure is applied to each pin as we work our way from the back pin, to the front pin... or we might work

from the front to the back. Whatever pattern you prefer, it will likely have to be repeated several times over before the lock opens.

SWEEPING Here, we start at the back of the lock and lightly run/pull our hook over the pins to the front in order to locate the binding pin.

With this motion, our hook tends to kind of catch, snag, and stop at the solid binding pin. Sweeping is a wonderful time saver.

It allows us to quickly zero in on the pin that needs to be targeted, while wasting no time on the pins that are not yet binding.

I love this technique! Sweeping is almost always my initial attack when it comes to nearly any lock. But using this method with

Americans places me in the minority. The majority of people I see picking an

American lock usually prefer pattern testing...

and with good reason. When it comes to picking serrated drivers (or spools), there's a downside to using this technique...

- Imagine the state of a pinstack where the driverpin has been lifted onto or past one or more serrations.

That driverpin will then bare the spring load, leaving the keypin beneath it 'free-floating'. I call these 'hangers'.

For us, when we come across a free-floating keypin (no springyness), we usually assume that particular pinstack has been set.

This means we could potentially glide over a keypin, and not realize the driverpin above it is binding. So even though a keypin

may feel loose, its' driverpin may still require additional lifting past several more serrations. If you don't truly set each pinstack

the VERY FIRST time you come in contact with it, you'll leave behind a 'hanger' that will have to be found later.

For this reason, I tend to use both methods depending on how things are going. If I've swept through a lock, and it's

not popped after a short time with this method, I'll revert to pattern testing to finish it off. I suppose this would be

similar to a competitive picker who sets what he can using a rake, then switches to a hook to get any remaining pins.

LIFTING pinstacks is a thing of preference as well. I mainly see (and use) two main techniques.1. You may opt to lift each pin in one continuous, motion. This way of lifting a pin is pretty straight forward,

and probably doesn't require much more explaning than that. A constant yet consistant lifting force is applied,

and the pin is gradually brought to the shearline in one fluent motion.

2. The other option is to 'bounce' your pick. Using the word bounce to describe this technique is probably not

the best idea, as it implies a sort of 'out-of-control lift'. Quite the contrary. What we're doing here is applying

a very controlled and consistant lifting force to the pin. But instead of the force being continuous, it's delivered

to the pin in a rythmic/pulsating fashion. A more appropriate word might be 'nudging', since that's basically

what we're doing; nudging the pin little by little until we hit the shearline.

Both of these methods can work well. Or, you may find your own style that works better for you.

But regardless of how you decide to lift, you

must keep in mind what we discussed earlier - finding

and MAINTAINING that

optimal lifting force that creates that

perfect threshold. I know I'm getting

redundant with this but it is by far the most important thing I've mentioned in this article. Like it or not,

I've taken it upon myself to beat the livin' shit out of this horse from every angle until you get the hang of it.

Feel free to ask, and I'll be more than willing to pick up my beatin' stick again...lol. But this should about do it.

Lets say for example you're working on a pinstack. You've heard and felt the 'clicks' and know you've lifted it past several serrations.

All of sudden that SAME lifting force you JUST used to pass those previous few serrations does not seem adequate enough to lift the

pin any farther. At this point, a red flag should go up! The state of the pinstack has changed; it's no longer responding to our 'optimal

lifting force'. This means the pin is set and any further lifting will result in an overset. It's time to leave it alone and move on.

In addition, this may be accompanied by a couple of other tell-tale signs (sight & sound). But, as we discussed earlier,

these are dependent upon the condition of the lock and the amount of tension you're using. You may have noticed the

final 'click' was a slightly more pronounced 'snap' in comparison to the first two serrations that you past. You may also

notice the entire core moves upward within the lock body as you test the pin a bit more.

Our first encounter with serrated drivers can be frustrating.

Our natural tendency is to want to "

lift just a LITTLE harder"........or, "

I think I can get just ONE MORE CLICK out of this pinstack".

The result is always the same... an overlifted pinstack. Train yourself to stay within that optimal lifting force.... no more, no less.

This force will not be sufficient enough to push a pin beyond the shearline, hence... will not ALLOW you to overlift. On the other

hand, some of us are so fearful of overlifting that we don't lift far enough... leaving you with those annoying 'hangers'.

Again, if you have found the correct lifting force, you can test pins all you want without fear of overlifting them.

Know Thy Enemy . . .

Know Thy Enemy . . .

and is designed to get

and is designed to get

yep, sticky it!

yep, sticky it!